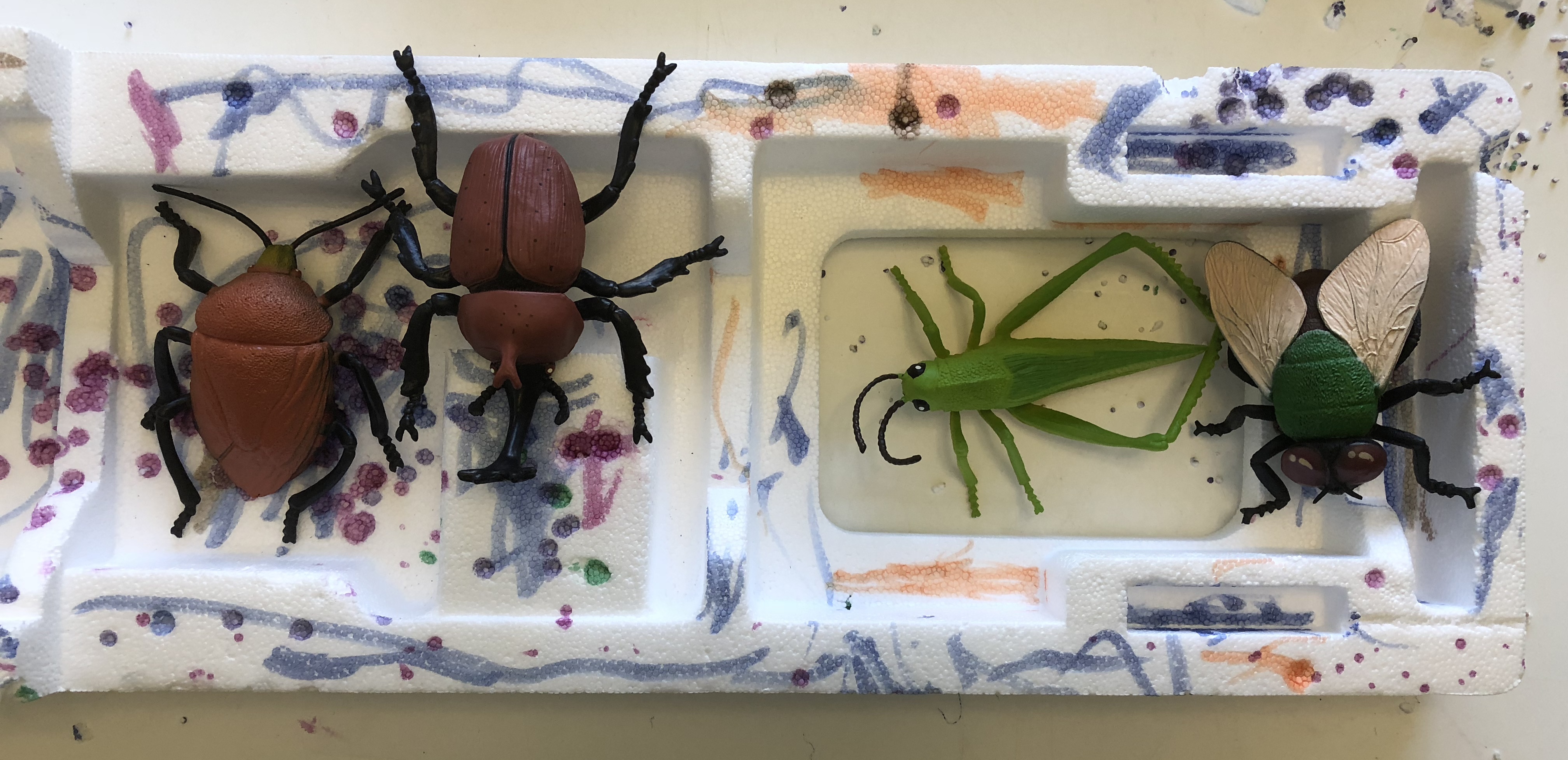

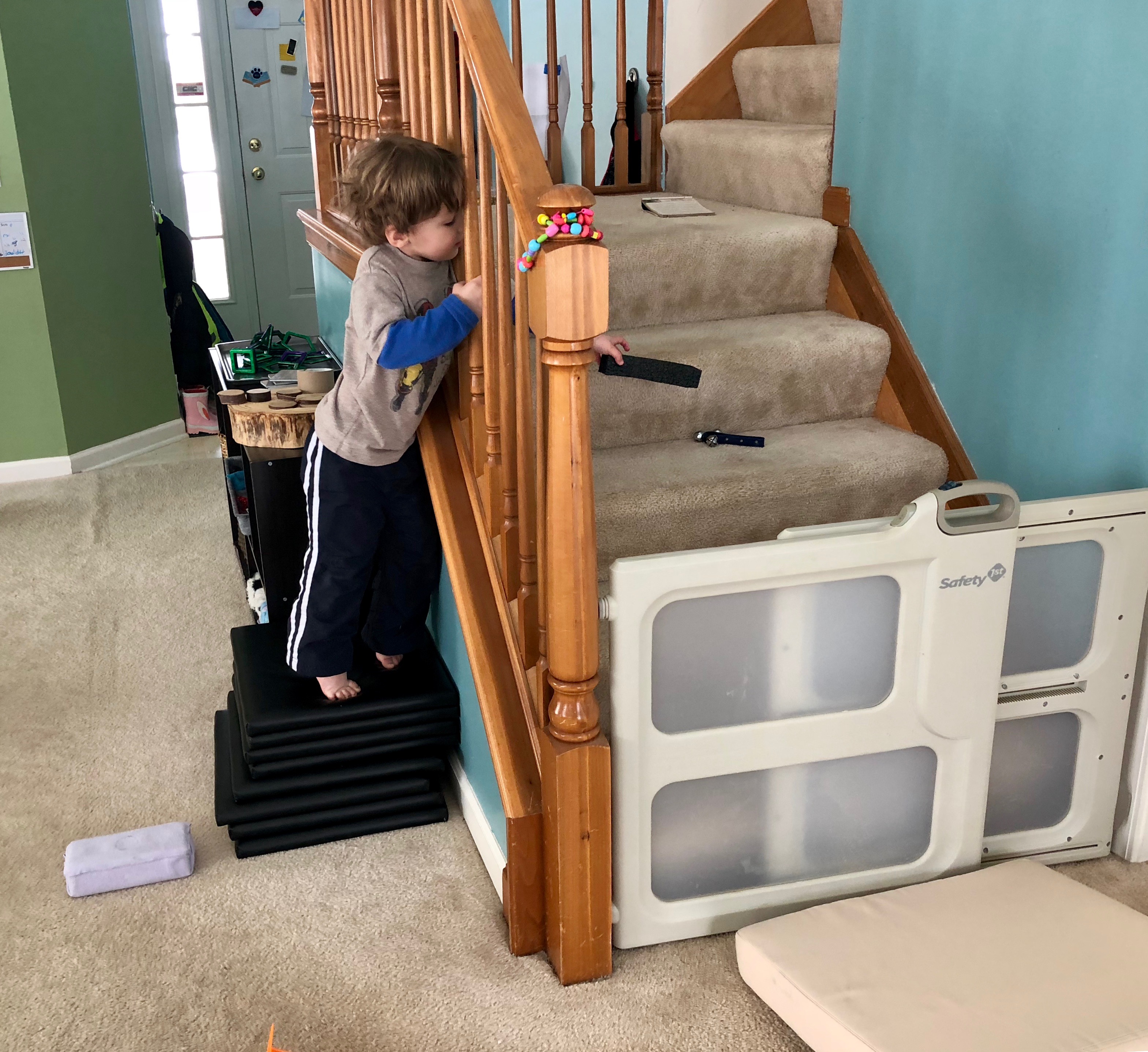

Emily and Kathrine: “Ants! Ants! Hey! They are flying!”

Me: “I see fruit flies!”

Emily: “I think they’re called fruit flies because they like fruit.”

Katherine: “They do like fruit! I’m going to go look for some more fruit. Ta-da! I found a potato!”

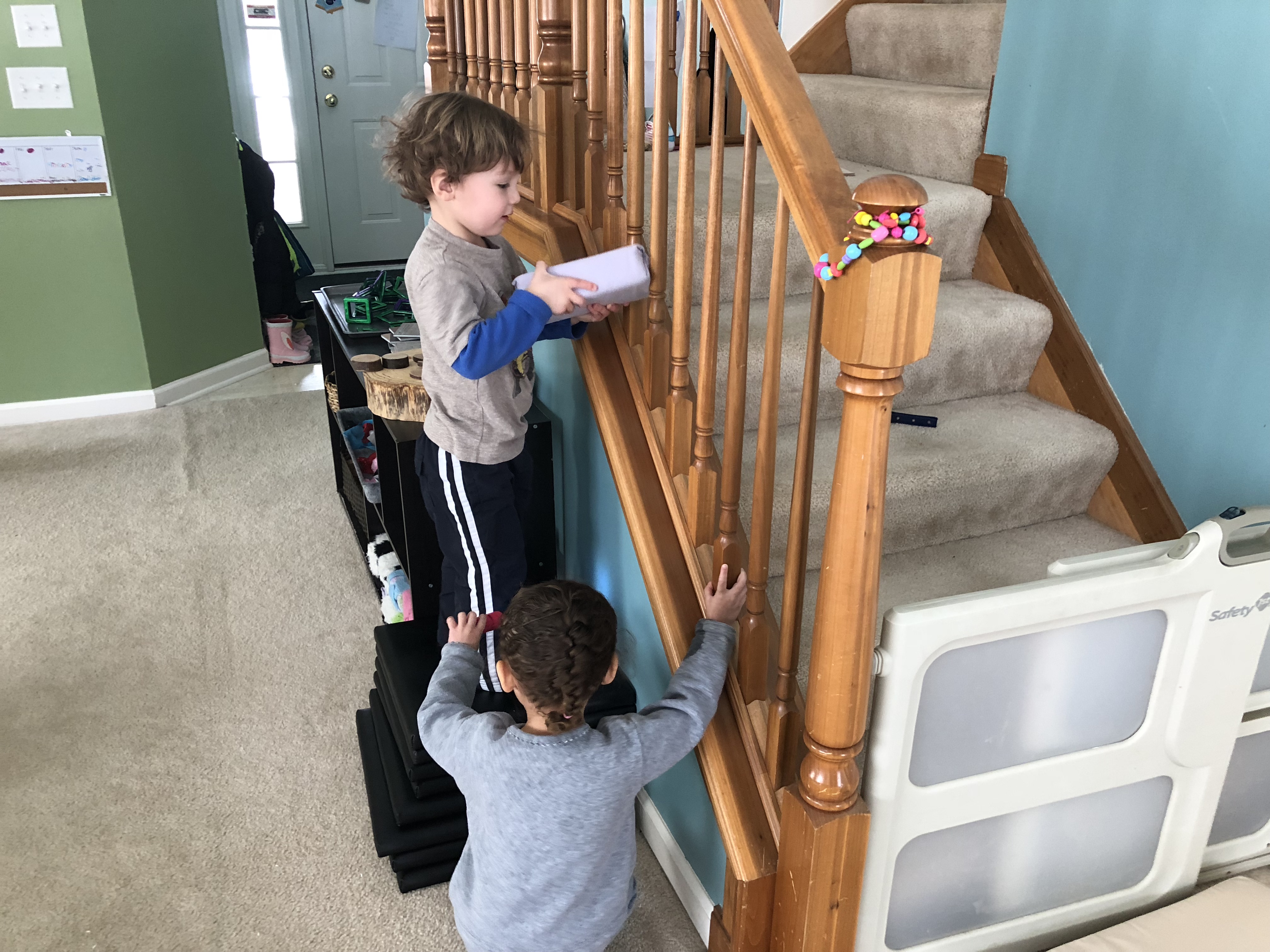

Emily: “Jake! C’mere! We found fruit flies. We’re finding some things for them to eat. Do you wanna to look for food too?”

Emily: “I’m gonna go find some leaves for them!”

Katherine: “But they don’t eat leaves?!”

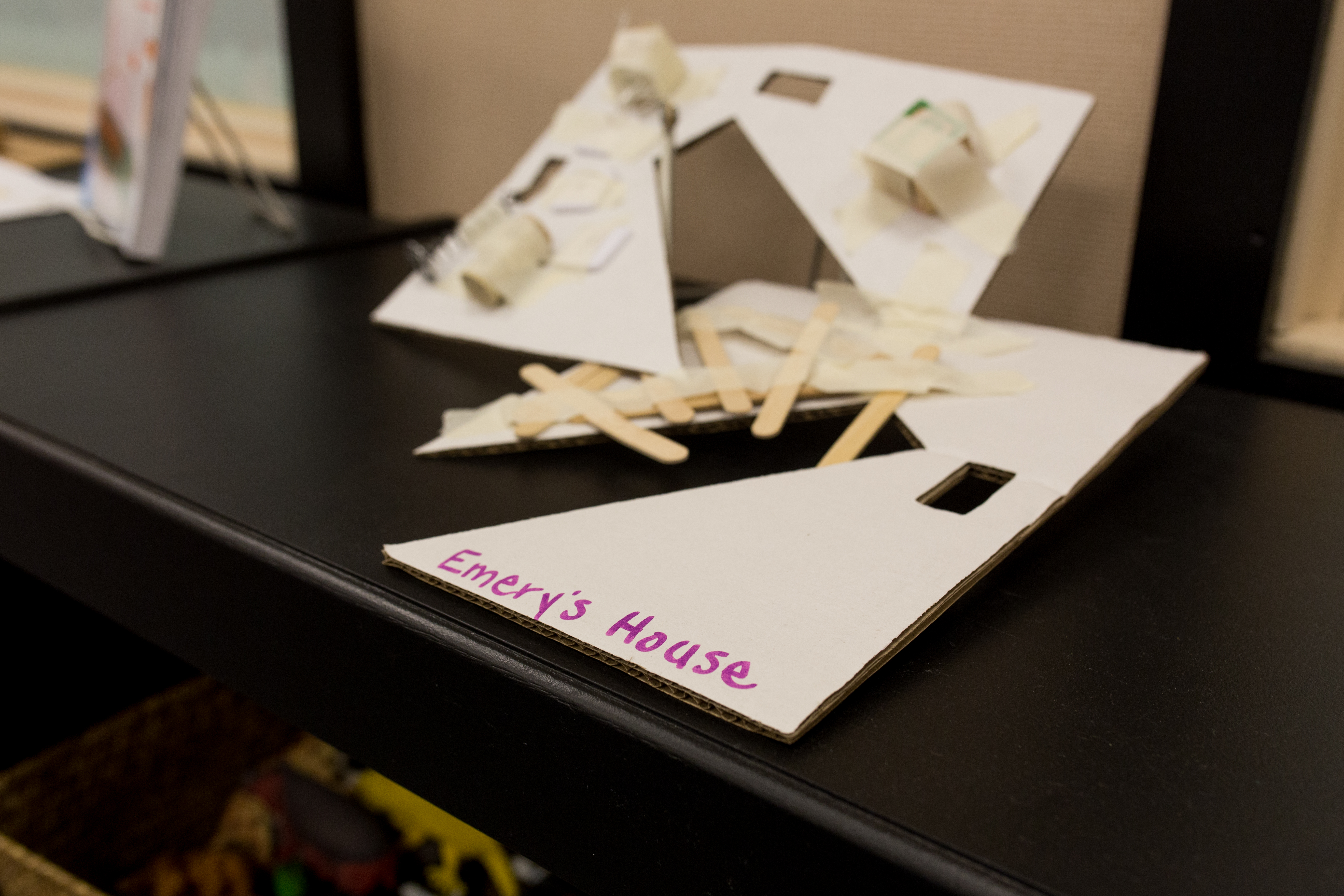

Emily: “I’m building their home. This is their bed. This is a fence to keep them safe.”

Emily: “This leaf looks like a green bean, so I think they’ll like it.”

Emily: “I’m gonna go check on the bugs…Yep! They’re still here!”

Me: “Do you see the same number of bugs, more bugs, or fewer bugs?”

Emily: “There’s more! You guys! Come look! There are more bugs now!”

Katherine: “They can eat these things up. When they’re hungry, they can eat it all up!”

When I opened up the Indiana DOE Early Learning Foundations alongside this learning story, I was surprised to find that Emily and Katherine demonstrated 29 developmental skills across 8 learning domains!* I can say with confidence that I have never written a lesson plan or designed an exploration that intentionally covered that many learning objectives.

Despite that, educators are expected to create lesson plans and activities — not built on the learning strengths of their students — but on their deficiencies. This deficits-based approach leaves many teachers and families feeling worried that they are not doing enough to help their young children succeed.

When we focus all of our attention on the knowledge or skills that our children don’t have yet (i.e. what they are working on), it’s easy to lose sight of the capable children who are standing right in front of us. We forget to celebrate, we even downplay, the valuable contributions that our children are currently making in our families and in our communities.

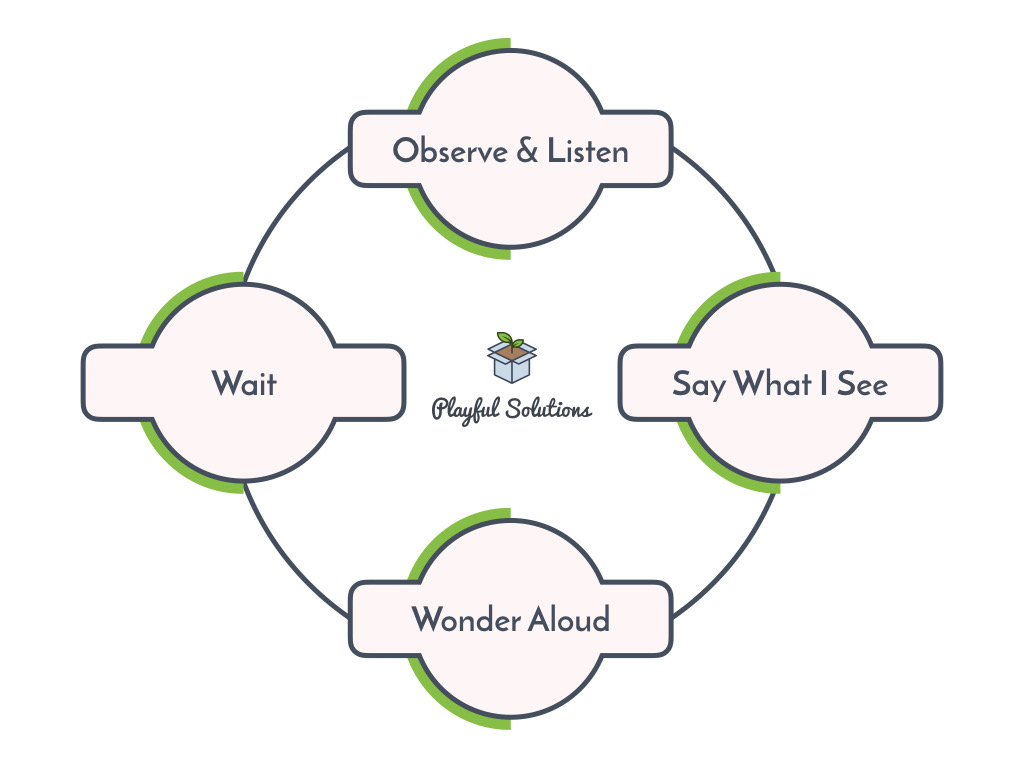

Children are self-motivated to learn what is most meaningful to them right now, regardless of any lesson plans we have prepared. The challenge is to first identify developmentally appropriate skills in the absence of any direct instruction, or “in the wild.” Only then can we truly challenge our children to stretch their skills and their knowledge.

In the story of the fruit fly house, Emily and Katherine combined their current knowledge and skills to solve 2 meaningful problems: hunger and homelessness. Think about that for a minute. At 3 and 4 years old, these children recognized hunger and homelessness as a problem. Emily and Katherine identified the problems and acted on them without hesitation, confident that they could fix it by using the resources around them.

They collaborated with one another and challenged one another. They reached out to others who they thought might help them. They also practiced flexibility and perseverance in the face of obstacles. These are all skills that will prepare them for the “rigors” of elementary school. More importantly though, these life skills allowed Emily and Katherine to engage as confident and active citizens within their current learning community!

Life skills like these are often overshadowed or abandoned entirely in favor of skills that can be taught and quickly tested by an adult. It’s easy for us to teach a child how to identify their name or to see if they know 1+1=2. Children however, naturally learn concepts like addition long before anyone tells them that 1+1=2. They discover it simply by exploring the world around them.

If I had only been looking for Emily and Katherine to demonstrate that particular math skill, I would have failed to see the other five math skills that Emily and Katherine did demonstrate in this learning story. By observing and recording the learning story first, and then comparing it back to developmentally appropriate standards, I could see that Emily and Katherine were not just playing. They were actively exchanging knowledge and integrating 29 distinct developmental skills “in the wild.”

If you are worried that you are not doing enough for your children, I encourage you to look at what developmentally appropriate expectations look like in early childhood. Instead of looking for all of the knowledge or skills that your children do not have yet, identify what they can do independently. I guarantee that they did not learn any of those skills purely through direct instruction or rote memorization.

If you, like me, are an educator who believes in the power of child-led learning, this challenge remains. How do I effectively communicate the value of my observations to others who do not yet see the connection between play and learning? I would love to hear your thoughts! Feel free to drop me a message at: crystal@playfulsolutionsindy.com

*Source: https://www.doe.in.gov/standards/indiana-early-learning-foundations

Foundations Observed

English/Language Arts Foundation 1: Communication Process

- ELA 1.1-2: Demonstrate receptive and expressive communication.

- ELA 1.3: Demonstrate ability to engage in conversations

Mathematics Foundation 1: Numeracy

- M1.3: Demonstrate recognition of number relations

Mathematics Foundation 2: Computation and Algebraic Thinking

- M2.2: Demonstrate awareness of patterning

Mathematics Foundation 3: Data Analysis

- M3.1: Demonstrate understanding of classifying

Mathematics Foundation 4: Geometry

- M4.1: Demonstrate an understanding of spatial relationships

- M4.2: Demonstrate an ability to create and compare shapes

Social Emotional Foundation 1: Sense of Self

- SE1.1: Demonstrate self awareness and confidence

Social Emotional Foundation 2: Self-Regulation

- SE2.1: Demonstrate self control

Social Emotional Foundation 3: Conflict Resolution

- SE3.1: Demonstrate conflict resolution

Social Emotional Foundation 4: Building Relationships

- SE4.1: Demonstrate relationship skills

Approaches to Play and Learning Foundation 1: Initiative and Exploration

- APL1.1: Demonstrate initiative and self-direction

- APL1.2: Demonstrate interest and curiosity as a learner

Approaches to Play and Learning Foundation 2: Flexible Thinking

- APP2.1: Demonstrate development of flexible thinking skills during play

Approaches to Play and Learning Foundation 3: Attentiveness and Persistence

- APL3.1: Demonstrate development of sustained attention and persistence

Approaches to Play and Learning Foundation 4: Social Interactions

- APL4.1: Demonstrate development of social interactions during play

Science Foundation 1: Physical Science

- SC1.1: Demonstrate the ability to explore objects in the physical world

- SC1.2: Demonstrate awareness of the physical properties of objects

Science Foundation 3: Life Science

- SC3.1: Demonstrate awareness of life

Science Foundation 4: Engineering

- SC4.1: Demonstrate engineering design skills

Science Foundation 5: Inquiry and Scientific Method

- SC5.1: Demonstrate scientific curiosity

Social Studies Foundation 3: Geography

- SS3.1: Demonstrate awareness of the world in spatial terms

- SS3.3: Demonstrate awareness of environment and society

Creative Arts Foundation 3: Visual Arts

- CA3.1: Demonstrate creative expression through the visual art process

- CA3.2: Demonstrate creative expression through visual art production

Creative Arts Foundation 4: Dramatic Play

- CA4.1: Demonstrate creative expression through dramatic play

Physical Health and Growth Foundation 2: Senses

- PHG2.2: Demonstrate development of body awareness

Physical Health and Growth Foundation 3: Motor Skills

- PHG3.1: Demonstrate development of fine and gross motor coordination

- PHG3.2: Demonstrate development of oral motor skills

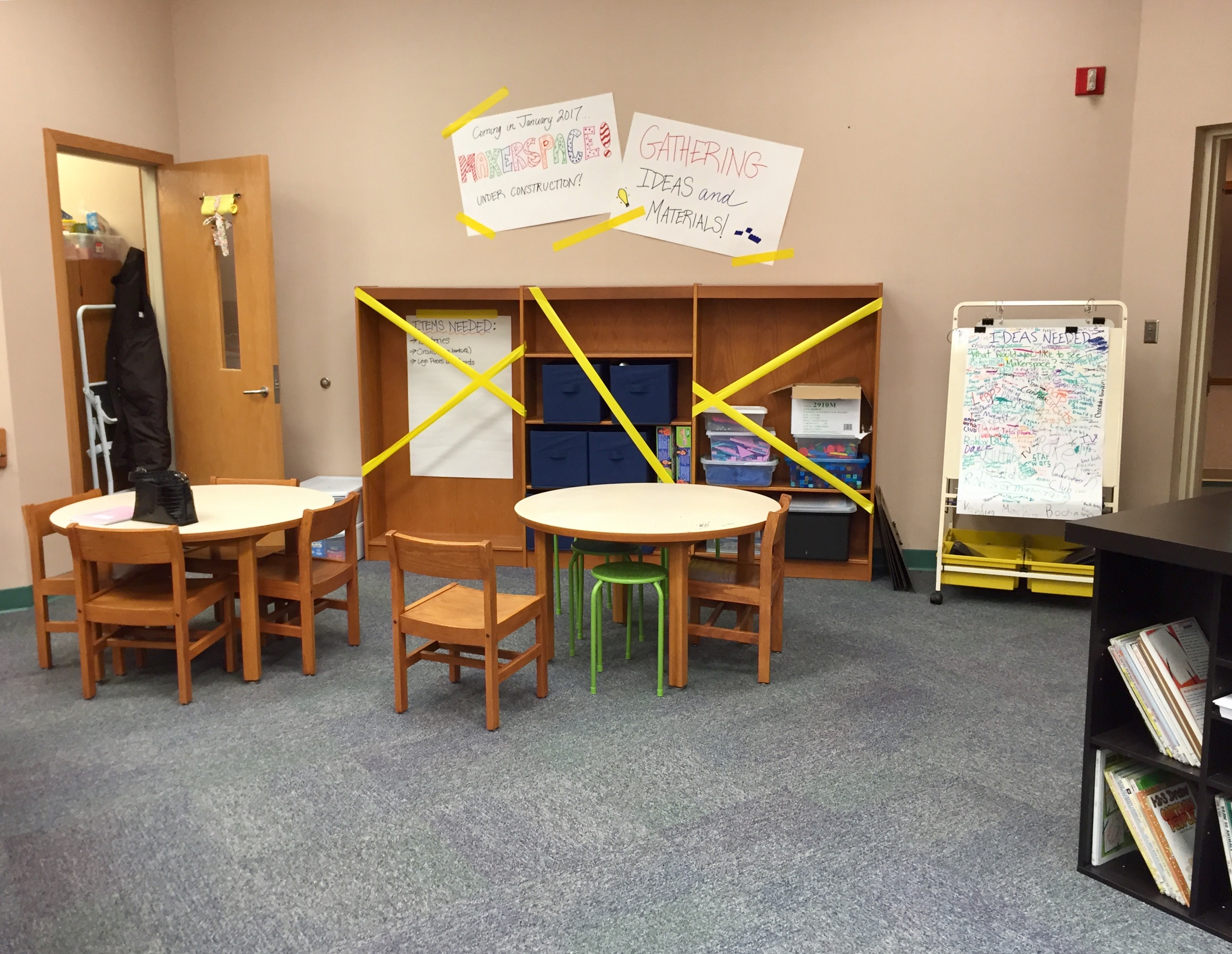

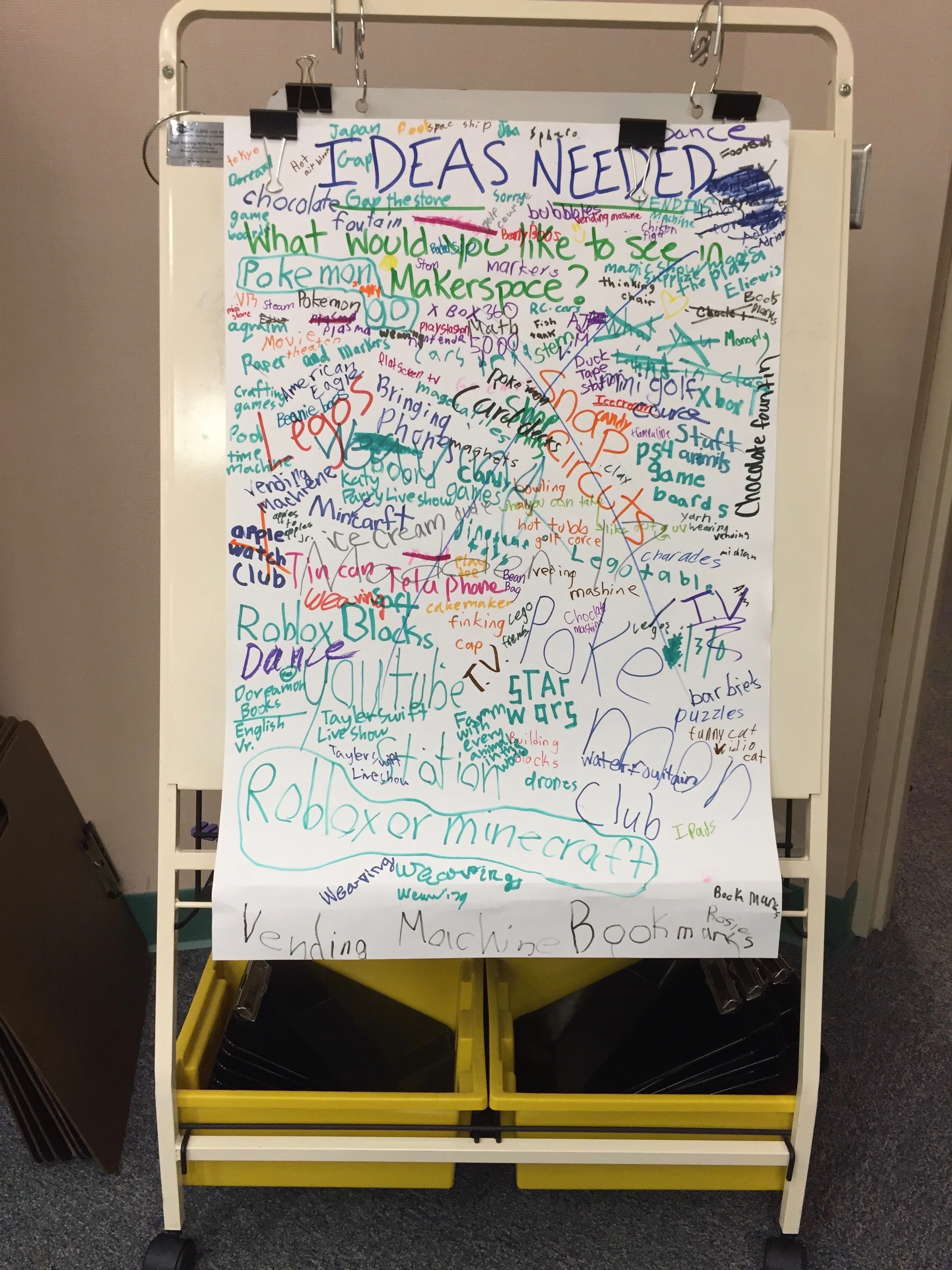

This project began with a tiny space and some BIG ideas! Lantern Road Elementary is a public school serving grades K-4 in Fishers, Indiana. They asked us to assist them in creating a maker space that reflects their unique school culture and values.

This project began with a tiny space and some BIG ideas! Lantern Road Elementary is a public school serving grades K-4 in Fishers, Indiana. They asked us to assist them in creating a maker space that reflects their unique school culture and values.