Henry (3yo): Calling into the drain, “MOMMY! DADDY! MA MA MA. DA DA DA. MOMMY! DADDY!” See, Miss Crystal?! MOMMY! DADDY! I hear it!

Me: I hear it! I hear an echo!

Henry: There’s an echo for me in there! It comes up from here. (pointing to the drain)

Me: The echo comes up from the drain?

Henry: Yes! Where are the other drains that have echoes?

Me: I wonder…I see a tube inside the drain that goes this way. (pointing towards the street) The tube goes under the ground. Let’s follow it! Let’s see where it takes us!

“There it is! DADDY! This one has an echo too! Let’s see if we can find more echoes!”

“I see one over here! No. This one does not have any water. It doesn’t have echoes too.”

“I see another one over there! No. That’s just a puddle.”

“Here’s another one that’s like the other one (The first drain). It has an echo too!”

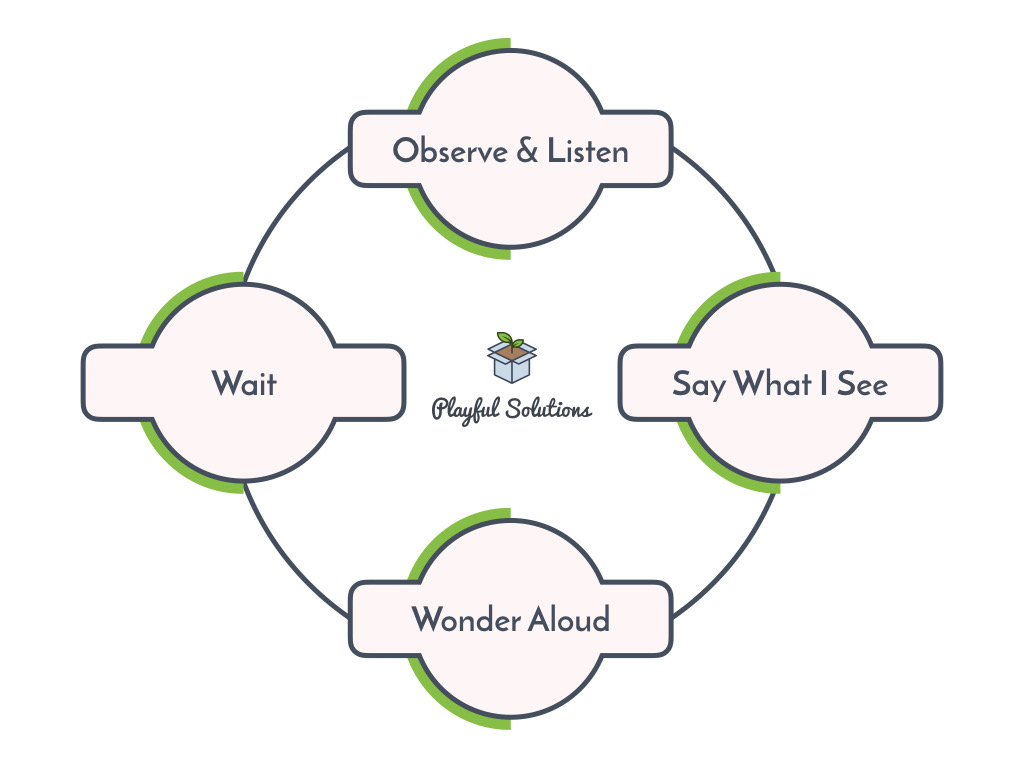

This is a sweet little story about finding wonder in the mundane, but there is also something else deeper. In rapid succession, my friend proposed a series of questions and wonderings. He tested them, and formed new theories based on his findings. Reflecting back on the experience, I can begin to piece together the spaces between Henry’s words and actions to see his theories.

Echo theories according to Henry’s current research:

- Echoes are a unique gift. There is an echo for me and there is an echo for you, but they are not the same echo.

- The origin of an echo lies inside of a drain.

- If you find one drain with an echo, there must be more drains with echoes nearby.

- Echoes only come from drains if they have water in them.

- If you find a drain that looks the same as another drain with an echo, it will also have an echo.

- Echoes do not come from water that is not inside a drain.

Henry’s theories of echoes are not all scientifically proven yet, but that is the nature of theory and inquiry. Theory is designed to be continually challenged. The goal of scientific inquiry is not to find the “right” answers, but to use answers as a springboard to the next set of questions.

“Is it possible to ‘see’ an echo?”

“Can an echo live outside of a drain?”

“Can an echo live in a tree? In the sky? In a cave with a bat?”

These are the questions that Henry is currently investigating.

His enthusiasm for echoes is contagious! Other friends have begun to join in the experiments adding their own unique points of view and questions to the mix.

One of the most beautiful qualities of inquiry-based learning, is that there is no end. One discovery, one question, one story leads to another and another. The depth and breadth of the exploration is entirely up to Henry and I’m excited to see where his echo theory takes us next!